Student Mental Health: An Inside Perspective

A high school student today experiences higher levels of stress than an asylum patient would have in the 1960s. This is a statement that many have heard and brushed off in passing. However, according to a study performed in 2000 by Dr. Jean Twenge, there is truth to these words.

Her opening paragraph in the case study, Age of Anxiety? Birth Cohort Change in Anxiety and Neuroticism includes the line, “The average American child in the 1980s reported more anxiety than child psychiatric patients in the 1950s.”

The global mental health crisis has gained more recognition as the stigma around psychiatric disorders has lessened. Still, mental illness among today’s youth as they grow up in a time of uncertainty and constant change has yet to be entirely accepted as the growing complication that it is.

According to the 2021 statistics manual by Mental Health America, approximately 13.8% of adolescents reported suffering from at least one depressive episode within the last year — an increase of 206,000 youth who reported having an episode, as opposed to the data from the year prior.

Severe major depression increased by 126,000 in juveniles, and about 4% reported struggling with a substance abuse disorder within the past year.

Furthermore, personality disorders such as borderline personality disorder (BPD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have increased among high school-aged youth. Unfortunately, mental health professionals are reluctant to diagnose young people with personality disorders like these in hopes that the patient’s disorder is transient.

These illnesses impose a severe obstacle, not only for the people going through the experience themselves, but also for those who surround them and don’t have proper resources to aid them in recovery.

In addition to the dramatic growth of disorders in students, academic stress has also been rising for some time.

“The academic pressures and stress faced by teens today start long before high school and seem to escalate every year,” writes journalist Andrew Simmons in an article for Edutopia.

“The pressure comes from parents and educators who worry — and make teenagers worry — that they won’t get accepted into highly ranked universities with increasingly prohibitive tuitions or be prepared for a competitive job market once they graduate,” Simmons adds.

Because of society’s pressure for children to excel in everything they can academically, chronic anxiety associated with school poses a significant risk in students, especially in America.

“Research shows that academic stress leads to less well-being and an increased likelihood of developing anxiety or depression,” shares Jason Hooper, president of behavioral healthcare and child welfare organization KVC Kansas. “Additionally, students with academic stress tend to do poorly in school,”

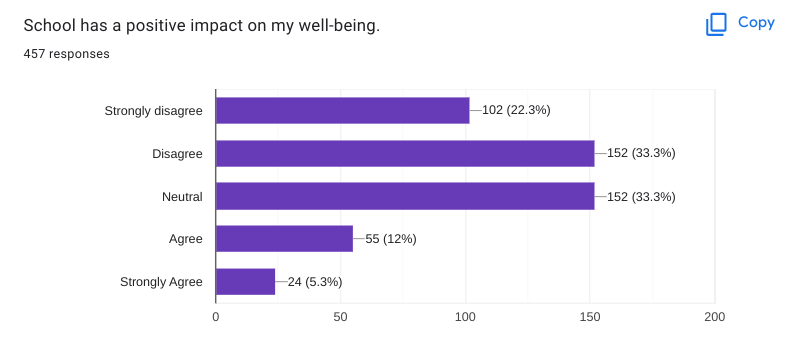

The Bengal’s Purr surveyed the LHS student population in this fall to see if academics and stress were connected. The results were astonishing.

About a third of the LHS student population responded. Out of those 457 students, 75% reported feeling stressed often; 79% reported that school adds to their overall anxiety; and 55% reported that school does not have a positive impact on their well-being.

In addition to poor health and stress management, 18% of students surveyed struggle with classwork, and 33% worry they are behind their peers at school. To top it off, 50% of students surveyed reported that they don’t feel positively about attending school.

When prompted with the question, “What would you tell teachers or staff about mental health?” students anonymously gave insights into what they believe contributes to the state of students’ mental health and how teachers can aid them.

“Many students struggle extremely despite all of the available health resources because of some teachers not paying enough attention to their individual students. However, I believe that the root cause of mental health issues in our school is the large class sizes and lack of student participation in class. School should feel less like a chore and more like an interactive community,” shared one student.

“Giving the extra effort to make learning fun and make sure people don’t feel stupid when they are behind makes all the difference,” said another.

Students who responded in the survey proved a correlation between not only their academic performance and their mental health, but also a correlation between their happiness, the relationships they form with their mentors, and the environment they learn in.

In their written responses, many students claimed they wanted to urge teachers to put more time into the relationships they form with students so they can better understand the individual issues students are working through, and also what might be happening within the student community that could affect them in class.

“I feel that many teachers/staff have no sympathy for students when it comes to how tiring school and life combined can be,” wrote one student.

Another response articulates the importance of peer-mentor relationships;

“I would want to let teachers know that they have a bigger impact on children than they might think. Both positive and negative.”

According to The Education Trust, “Strong relationships with teachers and school staff can dramatically enhance students’ level of motivation and therefore promote learning.”

When asked whether they feel as though their teachers value them, only 36% of LHS students responded positively.

This is a trying time for everybody in the world, but especially for students who are constantly barraged with the anxieties of academic performance, relationships and personal mental health struggles. Now more than ever, the adults who students look up to as role models should take more time to consider how hard kids are trying. They are trying to be the best they can be in a society that’s going to shambles. Kids and their mentors need to work together to stay strong for themselves, and each other.