In recent years, the popularity of STEM has continued to grow, and the availability of career opportunities within science, technology, engineering, and mathematics has become increasingly greater. According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, the STEM workforce has grown by 5.9 million from 2011 to 2021, representing a 20% total increase in one decade. Employment projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show an expected growth of 8% for STEM occupations by 2029, compared with an increase of just 3.7% for all trades overall. This data is both impressive and exciting to those looking to pursue a career in these industries, as well as the general public as a whole, who will inevitably benefit from this increase in the labor force and the abundance of new scientific discoveries and breakthroughs that will come along with it.

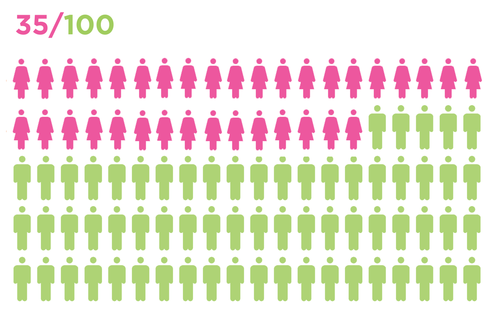

However, this growth also draws attention to the alarming gender gap within STEM professions and the lack of representation for women and minorities in scientific occupations. A report conducted by the National Science Foundation found that just a few short years ago, in 2021, “about two-thirds (65%) of those employed in STEM occupations were men and about one-third (35%) were women.” According to the American Association of University Women (AAUW), a non-profit organization that works to advance equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research, “Men in STEM annual salaries are nearly $15,000 higher per year than women…And Latina and Black women in STEM earn around $33,000 less…”

Representation, or the lack thereof, from the educational perspective, is even more disturbing. According to the National Girls Collaborative Project, a non-profit organization that aims to expand representation in STEM and increase the engagement of women and girls in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, “Women earn a majority of bachelor’s degrees in psychology, biological sciences, and social sciences, but they earn only 24% in engineering, 21% in computer science, and 24% in physics.” Furthermore, “Latina, Black, and Indigenous women earn [just] 14% of bachelor’s degrees in STEM fields.”

These staggering statistics raise questions about where our society and institutions have gone wrong, resulting in this enormous disparity. The answer? There are, in fact, many. The first is what is referred to as the “confidence gap.” The confidence gap is a term used to describe the rapid loss of confidence in mathematical and scientific abilities that many girls face as they age. “Many girls lose confidence in math by third grade. Boys, on the other hand, are more likely to say they are strong in math by 2nd grade, before any performance differences are evident,” said the AAUW. This gendered math gap is in correlation to other common factors, such as income and race: “Girls score higher than boys in math in lower-income, predominantly Black areas, but their scores are still disproportionately low compared to scores for white boys in high-income areas.”

Other significant issues contribute to this disproportion as well, such as the lack of role models, male domination, and gender stereotypes. There is an overabundance of male role models in STEM, while many major female contributors to the advancement of science and technology remain hidden behind the scenes and have yet to be brought to the forefront where they rightfully belong. Additionally, studies have proven that women in STEM positions are often presumed to be incompetent when compared to their male counterparts, and successful women in their fields are considered significantly less likable than successful men in the same occupation. Finally, the math abilities of young girls are often underestimated as early as preschool due to misconceptions such as the “math brain” myth, which assumes an innate cognitive, biological difference between boys and girls in math performance. “I would tell young girls who are interested in STEM not to feel like they have to fit any sort of stereotype…You don’t have to fit into any mold,” said Kate Pernsteiner.

Pernsteiner is a homeschooled senior looking to pursue a a degree related to nuclear energy or chemical engineering post-graduation with an interest in working with energy solutions in the future. “I believe STEM education is very important! I think anyone should learn, but getting more female involvement would be nice as it is predominantly male,” said Pernsteiner.

Although the existence of these systematic problems is irrefutable, there are a wide variety of solutions that, if implemented, could promptly lead to remarkable improvements. Many of these potential fixes start at the educational level. For instance, schools can begin by cultivating a respectful environment that is unassuming and equitable to all, regardless of gender. Teachers and professors can clarify performance standards and expectations to avoid reliance on stereotypes as a benchmark. Perhaps most importantly, we can encourage girls to get involved in STEM, to explore their interests, and, to seek out opportunities related to their passions. “Always be on the lookout for opportunities—there are so many. Get involved in programs…because they allow you to network and meet people with similar interests, or go talk to a professional in your desired field to see what it’s like and maybe get an internship. Hands-on experience is so important in the STEM realm,” said Maya Conklin.

Conklin is a senior at Lewiston High School seeking to earn her degree in physics from Montana State University while gaining her flight certifications in the off-time with the ultimate goal of becoming a corporate pilot. “My dad flew 1. My dad flew F-18s for the Navy—he inspired me to pursue a career in aviation,” said Conklin. Although meeting obstacles along the way, she is driven to succeed in her goals and remains confident in her passion: “Getting started is the hardest part, and trusting the process has been a challenge. I’ve learned that having a plan of action is important—but there’s also value in being flexible and working through life’s craziness with an understanding that it will work itself out.”

From all the struggles faced by women throughout scientific history, one thing is made abundantly clear: women in STEM are nothing if not resilient. The most important thing we can do to support their advancement is to show support for their efforts, uplift their voices, and highlight their achievements. There is undoubtedly a long road ahead to reaching an equitable future for women in STEM, particularly women of color in STEM. Still, the current outlook is full of hope for progression. “As a woman pursuing a career in STEM, I believe that there will still be opportunities for me and those like me,” said Pernsteiner. “And that those opportunities will continue to increase as there is more awareness for women in STEM.”