America’s history of deeply-seated racism is well documented through all forms of media. The history of the United States is available through a multitude of mediums is available to every American citizen if they choose to seek the information. Despite this, many citizens in this country argue against the very existence of racism within America’s political and social systems. Peer-reviewed scientific research and the United States’ policies and laws, both past and present, quickly dismantle this narrative.

Racism has impacted almost every American principle and advancement. A prime example of this everyday impact is America’s industrial development: the building of cities and suburbs, and road and highway infrastructure affecting minority groups. According to the World Economic Forum, “Black communities will see the flood risk in their neighborhood climb at least 20% over the next 30 years”. This statistic is derived from a graphing system developed to quantify and map street-by-street flood impact– and the United States is already experiencing the truth in this statistic. Exhaustive amounts primary research have been and are being published still about how the horrors and aftermath of Hurricane Katrina were exasperated by preexisting infrastructure and policy gaps affecting areas that housed black people and people of color. In fact, the Joint Center published a study in May 2008 describing racist practices “established patterns of settlement” in less desirable lands. Even though blatant housing discrimination practices don’t seem prevalent in society today, the permanent effects of these practices have forever tainted targeted communities, and are still easily recognizable in this day and age.

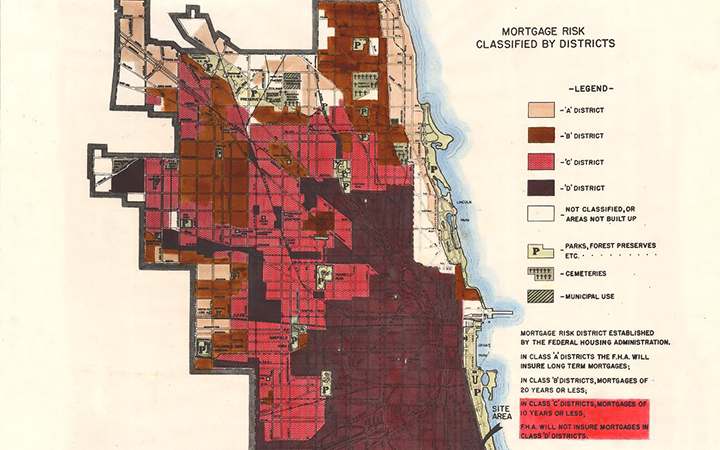

The Federal Reserve History website describes redlining as “denying people access to credit because of where they live, even if they are personally qualified for loans.” According to the History Channel’s website, when Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal passed in 1933, the National Housing Act was passed as part of the bill. Through this, an institute called the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) came to operate. The FHA classified neighborhoods in A, B, C, or D districts in partnership with the Federal Reserve. Class A districts were considered “lower-risk,” as classes B-C were classified as “higher-risk,” according to the Federal Reserve History.

The term “redlining” comes from the maps the FHA provided to banks, where ‘A’ neighborhoods were outlined but left white. Meanwhile, subsequent neighborhoods were colored in various shades of red to indicate their risk level. The FHA controlled the mortgage loans banks provided to citizens in response to the Great Depression and the following housing crisis. The FHA’s chief directors advised banks to provide “economically sound” loans. The principle of a loan being “economically sound” relied on the notion that the neighborhood of a house with a mortgage being taken out on it would be prosperous within the next 15-20 years. Communities being targeted through these practices had the potential to “jeopardize” the value of a neighborhood, according to the FHA, so officials made sure to prohibit “the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended”, according to the FHA’s Underwriting Manual, published in 1938.

Predominantly Black and low-income neighborhoods were considered to have the highest risk for banks and the FHA. This placed the people in these communities into something known as a “restrictive” or “racial covenant.” Generally, a “restrictive covenant” is the preservation of land to protect the value of the land surrounding it.

In the early 1920s, this practice began to dominate real estate. Black people — who were also the poorest in society — were deemed to be a threat to the potential monetary value of a neighborhood. The FHA deemed these human beings as a threat to their (already failing) economy simply because they existed. Black Americans were blatantly denied access to living in “white” neighborhoods. The FHA noted in its 1938 Underwriting Manual that “infiltration of inharmonious racial groups” increased credit risks, leading to a disconnect between white and black neighborhoods.

As white people received government subsidies that encouraged them to move from urban areas to suburban areas, a phenomenon dubbed the “white flight” spread. Cities were quickly becoming overdeveloped and overpopulated. Though black people began to recover from these practices to some degree, cities became hotspots for employment. This led to the construction of highways and byways to transport those living in the suburbs to jobs in urban areas.

According to an interview conducted in 2023 with David Rufus by the American Civil Liberties Union, these roads were intentionally built over black communities, displacing and destroying the little sense of security that they were left with. As these communities were broken up, people were further displaced. According to the History Channel website, more than 475,000 households, and over 1 million people were displaced by the highways built following Dwight Eisenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. Highways began to overtake what were once thriving communities with massive architecture, like multi-lane roads, overpasses, giant concrete walls, etc. These were physical buffers between the white and black worlds.

In 1959, New York City’s construction coordinator was Robert Moses – who was responsible for most of New York City’s roads, tunnels, highways, housing projects, and parks, and whose influence reached far beyond city and state lines. Moses said in a speech, “Our categorical imperative action is to clear the slums. We can’t let minorities dictate that this century-old chore will be put off another generation or finally abandoned.” His style of architecture physically segregated Black and White communities. For example, Moses built bridges intentionally low so city buses – which were likely carrying poor minorities – could not pass underneath. Examples included the bridges connecting Long Island and New York City, according to National Public Radio (NPR).

The rapid urbanization of these communities has led to exponentially higher levels of chemical and particulate matter exposure for minorities living in them. Those levels are up to 152% higher according to a 2005 study published in the National Institute of Health’s journal. Not only this, but the more people there are in a city, the more expensive the basic costs of living are, as demand is high constantly but supply cannot meet it. These cities are where white people come to work. Though they do not live there, they are still contributing to demand, meaning that the prices are rising at a disproportionate rate. This can lead to those who actually live in the city falling into a perpetual state of poverty. That is a cycle that continues throughout generations.

Richard Bullard, an urban planning and environmental policy professor at Texas Southern University, noted in 2019 that “race is still the most potent variable” when it comes to quality of life. As he explained to The Revelator, this is because so many centuries of racism have been indoctrinated into law and policy. This has been normalized to the point that many people genuinely do not believe racism exists. Even though these practices were executed up to 90 years ago, their effects have not gone unnoticed.

To deny the existence of racism because a person claims they “haven’t seen it” is to practice willful ignorance. Just because institutions don’t actively limit one person and their own opportunities does not mean that the institution is “color blind.” It is not a coincidence that minority communities are typically poorer, subjected to more police interference, or punished more strictly and frequently by laws. It is not a coincidence that these communities who are screaming for justice are being ignored for not being ”credible” enough.

Before there is change, there must be acceptance. Before acceptance, acknowledgement. To deny the existence of racism within the institutions of America is to thwart the progress of every civil rights activist, every protest, every progressive law passed; it is to accept that indoctrination has gotten the best of education. The best way citizens can combat the years of propaganda and institutionalized racism is through educating themselves and going out of their way to learn the things not offered to them in their school systems; this applies especially to white citizens, who are intentionally shielded from the generational trauma their ancestors have inflicted in the name of the “American dream”- a dream that, very clearly, never included minorities.

It is important to remember that facts do not care about feelings. “Feelings” don’t change the hundreds of years of racism that have shaped so much of American identity. There is no question about whether racism exists. The question is whether or not the government and society have normalized racism enough to make it a fact of life. And if that is the case, is there really liberty and justice for all?

Categories:

OPINION: Systemic Racism is an Inevitable Truth

0

More to Discover