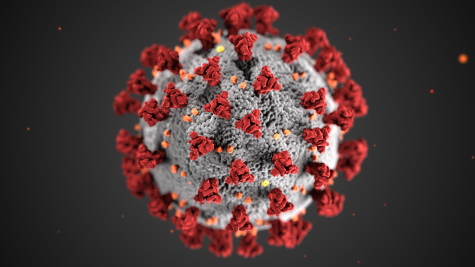

Student disengagement: A pandemic in itself

Students bored in class. Photo courtesy of smartsims.com

“Students seem to have lost their sense of connection with the university and the university community, and their sense of purpose in attending,” says Stephanie Masson, a professor of English at Northwestern State University. This statement captures a common theme throughout colleges, universities, and every other level of education across the country– a profound disengagement from students.

This disconnection between students and their education is the fallout of many things. However, professionals blame the more recent steep decline in student interest on the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 lockdown. It was so intense that the Institute for Youth, Education and Families (YEF) began a program called “Student Re-engagement After COVID-19 School Disruptions,” which focused on detailing different engagement strategies schools could use to rebuild their students’ interest in their class. Among these tactics were city organizations interacting with school districts, centers for learning for struggling students, and conversations highlighting the experiences of youth during the pandemic.

Their approaches to these strategies concentrated on “extensive research findings indicating that when formal learning settings lose their connections with young people, the young person and the community alike face harmful long-term effects on earnings, employment, housing and health that can last well into adulthood and put entire generations at risk,” according to the National League of Cities.

The pandemic has imposed a new level of disengagement in classrooms. Unfortunately, student withdrawal has been a recognizable problem since at least the mid-1980s — almost 40 years — and it certainly hasn’t spared the Lewiston-Clarkston Valley.

Disengagement has taken a severe toll on teachers everywhere, especially in the valley. Fifty percent of LHS teachers surveyed report feeling exhausted when they leave work and more than a third reported that they cannot see themselves as teachers for the rest of their careers. More than 50% of those teachers have also noticed that students don’t seem to embrace or overcome challenges. They observed that students struggle more to retain information, to turn in assignments, to speak out when they need help or to maintain positive attitudes.

Students from LHS weighed in and left the Purr with astonishing statistics. Out of nearly 300 students who responded, 67% reported seeing a difference between the way they see school pre-lockdown and post-lockdown. Likewise, 62% of students reported feeling overwhelmed by their coursework, 61% said they feel school is more of a necessity than an opportunity, and a mere 21% reported feeling happy at school.

A professor from Lewis-Clark State College (who has requested to remain anonymous) also noted a change in their students within the past few years.

“As a group [students] are very different, I feel… I find that quite a few students are more anxious and uncertain about their futures, which has made it harder to be in class and study,” the professor shared with the Purr. “I’ve taught for 20 years, and most students used to come to college with some excitement about learning and a future career, and most were full of confidence. Many students in the past couple of years don’t have as much confidence.”

This plunge in confidence is detrimental to a student’s learning ability. According to the Board of Health and Wellness in Malborough, Massachusettes, “Low self-confidence can make a child feel like [their] dreams are impossible to reach, or that [they] are unworthy of achieving these dreams.” When considered in unison with the lack of connection students have with their community at school, these changes in confidence become a foolproof plan for failure.

Dr. Charles Addo-Quaye, a professor of computer sciences at LCSC, reported seeing a drop in student motivation and a surge in mental health issues.

“Compared to the previous decade, there is an ascendency of student mental health issues that impact student learning,” Addo-Quaye said. “Also, students are less courteous, and feel more entitled, invest less effort in their course work.”

Cynthia Yarno, a French teacher at Lewiston High School, has also observed a lack of confidence and hope in her students.

“I feel like kids are losing hope, and that makes me so sad because I want them to have hope,” Yarno said, “because life is fun, and life is exciting, and I feel like they don’t believe me when I tell them that.”

Laura Vervain agreed. The fresh-out-of-college English teacher at LHS recounted a discussion with her colleagues about students’ lack of confidence in their futures.

“We talked about how we feel like students don’t necessarily feel like they can get anywhere in life the way that people in previous generations have been able to,” Vervain said.

She mentioned how the world around her students may seem desolate, leading them not to care about the difference they’re capable of making. She also said that students who have had a past with trouble-making might have a stronger feeling of hopelessness.

“I feel like [students] have almost given up, in a lot of cases, especially [students] who have had disciplinary trouble with school,” Vervain said. “They feel like, ‘Well, everybody already sees me as a troublemaker, I’m never going to make it through senior year intact, why should I keep trying?”

Numerous studies support the fears that educators have about student hopelessness leading to disinterest. According to a study published by the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, depression rates rose by 60% between 2009 and 2017 among adolescents between 14-17 and by 47% in elementary-aged children.

Student disengagement, continued…

Leonora Freelend, a math teacher for Lewiston High School, notes a change in her students’ willingness to speak up. While she does say that her engagement rate is dependent upon the make-up of her classroom, she does

note one surprisingly large difference;

“When I first started teaching, every night after school, I would have students in my room working on their homework. And, as the years have progressed, and I’ve been teaching for 25 years, I have fewer and fewer students come in either before or after school to work on their homework.”

Upon further discussion, she notes that less face-to-face interaction and feeling of community between her students may have led to the change in their motivation.

In 1985, Theodore Sizer and Michael Sedlak held an experiment in which they found that a considerable portion of teachers tend to undermine their students’ capabilities and thus decide to minimize the difficulty and amount of coursework given to their students. This, they claim, causes students to lose interest in the work they are given.

In 2004, Adena Klem and James Connell published an article titled Relationships Matter: While conducting this experiment, they found that 40-60% of students become “chronically disengaged from school” by the time they reach high school.

In the International Journal of Higher Education, a group of scientists banded together to find the complex factors that contribute to student engagement and published their findings. The paper goes on to say that disengagement isn’t a stagnant state- it’s “fluid” and can be exhibited by any student in varying degrees of severity.

It is clear that students and teachers alike are both seeing the effects of not only the pandemic but also the lack of regard and resources that the education system has provided for struggling learners and teachers for at least 40 years. Those on both sides of the student-teacher relationship must make more of an effort to acknowledge the problems contributing to these statistics, or the future of education will be grim.